|

I’ve been managing software development projects since the pre-internet digital dark ages. Over time I’ve seen software development process change as much as software languages and tools. (Maybe even more so — the Python language, first released in 1991, is in the middle of a data-science-driven renaissance.) It’s been fifteen years since I last used a waterfall software development process. You might think the last place you’d find that kind of “legacy” process would be an early-stage startup, but I still see startups (as well as mature companies) being pitched waterfall contract proposals by outside contractors to develop “Version 1” go-to-market software products. If you haven’t been doing software development for more than ten years, you may have never done “waterfall” development (or even know what it is). Regardless of project methodology, most software development follows a sequence of steps that look something like:

Waterfall methodology refers to planning and scoping all of these steps at the beginning, then executing each step in sequence. The workflow cascades in one direction, like a waterfall. Except when external constraints don't allow an agile approach (a government RFP process, say, or a large, hidebound enterprise), I have consistently seen better results through an agile approach: iterative, incremental, customer-conversation driven. Doubly so for a startup. Agile looks something like:

Tip: For existing products, substitute “feature” for “product” above. For brand new software, version 1 of the product may actually be an incomplete version “.5” that gets fleshed out through a customer feedback loop like the one above (more on this below). A product conceived by an elaborate design process, but not validated by actual customer engagement and feedback, may hit the mark on some product ideas but will inevitably miss the mark on others. Under a variety of circumstances over thirty-plus years I’ve never seen it play out otherwise. Several years ago I worked for a well-funded startup alongside very bright product managers, UI designers, and software engineers (several of whom went on to launch their own companies). Technically we were “agile” because we developed our software in sprints, but our feedback loop was internal. Rather than validate core assumptions with actual customers, we developed a full-featured “stealth” V1 (Version 1) of our product, a healthcare portal, that launched with much fanfare and a hefty marketing budget. With an all-star team and resources most startups can only dream of, we had every possible advantage. But because we did not include customer feedback in our process prior to launch, our product had about the same success as any other V1: some features resonated with users, but too many other features flopped. I joined this company at founding and saw it rocket to 300+ employees very quickly. It contracted back down to 20 employees almost as quickly. Why Waterfall? In the last ten years, thanks to Eric Reis, Steve Blank, and others, a lean startup approach emphasizing customer validation has become mainstream thinking in software development. So that begs the question: why do many software contractors still pitch waterfall projects? Let’s look at software product development from the perspective of a contract development firm. They need to manage project scope to make sure they fit a customer’s budget with enough room to make a profit. That’s pretty hard to do if you tell the customer, “we’re going to try out some things and see how they play with customers; we’ll iterate on that until we validate the design.” So even “progressive” software contracting firms wrap modern product-design in a linear (waterfall) project process by proposing something like:

Whereas as a client what you’d really like is a project that looks like:

Working Around WaterfallSo what can you do to promote incremental, customer feedback-driven product definition and development in the construction of your software? One option is to favor T&M compensation (time and materials, “paid by the hour”) over project-based compensation. T&M contracts are suitable when scope is uncertain, which it is when taking an “iterate until you validate” approach. It’s worth pointing out that an in-house team, if you have one, is effectively T&M. Some contractors provide dedicated engineers long-term on a T&M basis, either augmenting your own staff or operating as a self-contained, dedicated team; that’s one model that can jumpstart a new software development effort into an iterative development process. Make sure your contract allows you to terminate early and quickly if the vendor isn’t performing. If you don’t have in-house resources and you’re uncomfortable with the scope risk of a T&M contract, another option is to minimize the scope of your Version 1 project. Turn it into a Version .5 project, an incomplete version sufficient to validate your concept, and structure follow-on versions as separate projects. In addition to lowering your investment in un-validated product development, this approach incentivizes your vendor to perform to win follow-on work. To avoid misunderstandings, be clear about the incremental, feedback-driven approach you want to take with candidate contractors and make sure they’re amenable. However you structure your software development project, validate the initial concept with as little engineering investment as possible (consider low-effort approaches such as mockups or prototypes), and continue to vet changes through customer feedback. Don’t go chasing waterfall, even if you’re outsourcing, and especially if you’re outsourcing V1. Build customer-driven validation into your design and development process through an incremental approach. If outsourcing software development, make a phased approach a requirement for your contractor.

This post was originally published on WeWork Labs Insider and also appears on CTO Craft. See also Thomas Fuller's take on "extreme" agile development process.

0 Comments

No offense to software contractors, but given the choice I usually prefer to build software with hired employees. By signing on as employees, engineers demonstrate belief in the mission and commitment to the long-term success of the company. Often I can further align their interests with the company’s through equity as well as the opportunity to “grow with the company” in responsibility. On the other hand, I’ve been building software for over 30 years and managing software developers for 25. If you’re a non- (or not very) technical startup founder and need to build software, your needs may be better met by a software contractor. Compared to a permanent hire, advantages of contracting out your software development include on-demand resources; minimal overhead costs (benefits, equity, etc.); and flexibility in matching the scope of your resources to your project, making it easier to adjust your “team” as your needs change. These are advantages whether you’re managing your first software project or your tenth. The truth is, I’ve delivered many software projects staffed partially or entirely by contractors. I’ve sourced contractors through my professional network, Upwork, regular job boards, corporate recruiting departments, Slack channel conversations — you name it. Previously I wrote about taking delivery of your V1 software from a contractor. Here I lay out how I look at the entire software contracting process, starting from the beginning. Taking delivery is the third step: first come selecting, then working with, an outsourced software contractor. Selecting an Outsourced Software ContractorFinding the right contractor is not always easy for me and can be downright daunting if you’ve never done it before. At a high level, here are my decision factors: Individual vs Firm This is decision one: hire an individual coder or work with a contracting firm. Again, what works well for me may not be best for you. With less overhead than a firm, individual contractors can often offer their services at lower cost, and you are dealing directly with the individual doing the work. I’m comfortable managing software developers, so that works well for me. But a contracting firm offers advantages over an individual that may make sense for a non-technical executive:

Experience with your kind of project To evaluate a contractor’s experience with your kind of software project, you need a concept of what “kinds” of software there are, which may not be obvious if you’re relatively new to software development. Here’s how I break it down, again keeping it high level: Looks Good vs Works Good These are not mutually exclusive. But the skills needed to ace a corporate website are far different from those needed to build, say, a FinTech (financial technology) service. If your software is more like a corporate website, with primarily static content that needs to look good (e.g. "professional", "eye-catching"), you should be looking for a contractor with design expertise. Your project might benefit from a UI specialist up front. On other end of this spectrum, when developing an app or website with complex functionality, the most important thing (and hardest to get right) is that the software works. I’m not saying looks don’t matter, but if your FinTech platform is being built a contractor whose primary experience is building beautiful websites, be prepared to receive a beautiful application with bugs, scaling issues, or other functional problems. Look for a contractor whose experience matches where your project falls on the looks-good/works-good spectrum. If both are equally important in your project, both are equally important in (choosing) your contractor. Consumer vs Enterprise Serving different audiences, consumer and enterprise software are generally built with similar technologies requiring similar technical skillsets. Where they differ is in the product context that determines the requirements for the software. Here are my notes on the product context I associate with these types of software, that I look for in a contractor’s experience base:

Once again, look for a contractor with matching experience. Lifecycle Pricing When I’m budgeting a software project I think about the entire software lifecycle, my version of which I list below. Whether your software contract covers all of these steps or (most likely) just some of them, you should be thinking about how all of these steps get done, by whom, and how much they will ultimately cost:

Check References When I hire a contractor for the first time, I take one of two tacks:

I have found that references for a contractor will often share more information than references for a full-time hire. Maybe the stakes (or liability) seem lower. I try to make reference checks cordial and conversational. I’ve certainly learned things in those conversations I never would have picked up just looking at the contractor’s online profile or portfolio. A couple of tips for checking a contractor’s references:

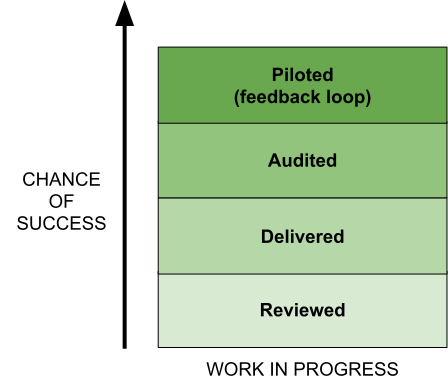

Working With Your ContractorBefore I describe this chart, let me first describe what I left off the chart. I omitted the easiest, least time-consuming, least intimidating mode of working with your software contractor: write a check, cross your fingers, and hope the final delivery’s good. It’s the equivalent of a Hail Mary pass and about as likely to succeed. WIP: Reviewed At a bare minimum, for any software project lasting more than a week or two, you should review your work-in-progress (WIP) software regularly during development, wearing your product manager hat. Have your contractor demo whatever they can. This kind of product review doesn’t require any technical knowledge on your part but does accomplish a couple of things:

WIP: Delivered Better than regular product reviews are regular deliveries of work-in-progress, even if you don’t do anything with them. Here’s what this accomplishes:

See below for more about taking delivery of software. WIP: Audited Better still than regular deliveries of work-in-progress are audits of work-in-progress: a hands-on examination of the software by an expert. This can include reviewing the software’s organization and readability and examining the technical decisions implicit in it. Findings from such an audit validate your contractor’s work in a more substantial way, giving you reassurance you’re receiving quality work (and an opportunity to provide constructive feedback if not). Another set of eyes on any technical work almost always improves the quality of the final result. A technical audit of your software is the only step that requires a technical friend, advisor, or consultant (like me) who is not your contractor. Assuming your in-house team is not technical, for this step you will need to find such a resource. WIP: Piloted The ideal way to treat your in-progress Version 1 is to launch early versions as a pilot, collect real customer feedback, and use that feedback to inform the product definition of the remaining development. Practically speaking this may be aspirational (as in not do-able) for some startups. Your product may require complete core functionality for customers to be able to use it. Your contract may not allow for changes to definition without incurring significant expense. But what’s the expense involved in launching a Version 1 that’s too far off the mark? Consider whether there’s a 70% version of your Version 1 that you could put in front of users. In my opinion the best software contracts include the flexibility to build even Version 1 software in multiple phases, allowing you to pilot intermediate versions and refine product definition based on real user feedback. Taking Delivery of V1The first time you hire somebody to develop software for you, delivery of the completed software feels like the finish line. In actuality, there’s only one scenario in which that’s true: when your company goes out of business right after you launch. Assuming that’s not your goal, Version 1 is the start of what will hopefully be long-term software ownership. That includes adapting the software to your evolving understanding of what your customers want, and simply keeping the software running smoothly through operational glitches, variations in user load, and external changes to infrastructure like your cloud platform. (For instance, Amazon AWS, the most popular cloud services platform, frequently updates their services and unofficially or officially deprecates old ones.) I recommend you take physical delivery of your software like a long-term owner-operator, even if your initial plan is for your contractor to continue to run it for you. These are the two things you should ensure are included in your contract software delivery:

I hear some version of “I’m about to take delivery of Version 1, what do I do now” as frequently as any other question I hear from non-technical founders. So I previously posted more about this all-important phase in the software contracting lifecycle. Don’t wait for delivery of Version 1 to start observing the best practices of successful software companies. Be diligent in your search and selection of a software contractor (even if you’re a small account). Structure your delivery into intermediate steps that you can leverage. Assume you and your software will be around for a long time, and act accordingly. Also published on CTO Vision and CTO Craft As a consulting CTO I work with companies at all stages of software product development. Startups with scarcely more than a PDF mock-up. Multi-million dollar businesses refining their umpteenth software version. But there is one stage in the evolution of a software company at which they disproportionately reach out to somebody like me — when they’re about to take delivery of new software from a software contractor. Like expecting a baby, you might think the imminent delivery of outsourced software would be a time of excitement and high spirits, but it is just as often a time of panic and confusion. I believe this consternation results from a couple of common misconceptions that non-technical executives become aware of as delivery day approaches. After all of the effort to conceive the idea, define and (maybe) validate a minimal viable product, weigh in-house versus outsourced development, shop for and choose a contractor, fund and schedule the software development, a software product owner’s attention finally turns to crossing the finish line — taking delivery of the software. Misconception #1: |

AuthorLarry Cynkin is founding principal of GreenBar. Larry's articles have appeared on The Startup (Medium.com's largest publication) as well as CTO Craft and CTO Vision. Archives

February 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed